05/02/2025

Amanda Lands In Forest Gate

I never thought when I bought my unremarkable terraced house in Chestnut Avenue, Forest Gate, in 1989, that one day a production company would choose it as a prime film location. But, much to my surprise, its diminutive hallway and traditional 19th century porch were just what Merman Productions needed for the new BBC1, six-part comedy series Amandaland, starring Lucy Punch as Amanda. It’s a spin-off of the cult drama Motherland, which starred Anna Maxwell Martin and Diane Morgan.

Nothing grand about the start of my flirtation with the stars though: a flimsy flyer stuffed through the letterbox, asking home owners to let the cameras in for half a day. I contacted the location manager and he asked me to take some shots of my front door. I sent them off and he replied: “Just what we’re after. May I pop round tomorrow for a better gander?”

Martin approved. “We want to film a bedroom scene, too,” he said. “We’d double the fee, of course,” he added as an afterthought. I knew Dame Joanna Lumley (who plays Amanda’s insecure mother, Felicity) was in the cast for this series. But I quickly dismissed any disgraceful thoughts of her occupying my bed for a scene or two. My shameful and ridiculous notion turned into a mere academic red herring as Martin was on the hunt for a teenager’s bedroom, which mine clearly wasn’t. Still, the fee for two-and-a-half-hours’ filming in the porch turned out to be more than adequate.

There remained the issue of the overgrown privet hedge. I asked him if I should give it a clip before the cameras rolled. He made it abundantly clear that long and straggly was the look he was after. So, thankfully, I was able to leave it uncut.

I was told that in this eagerly awaited sequel to Motherland, Amanda, who is in the throes of a divorce, has downsized to Harlesden. But apparently producers thought that unsung Forest Gate looked more like Harlesden than Harlesden did. So, E7 it was. There’s no stopping our beloved Forest Gate these days.

The first thing to happen on the day in question – 25 October – was the arrival of the art department (otherwise known as the props department), which consisted of two serious-looking chaps sporting neatly trimmed hipster beards. They deposited a brightly coloured football, a pair of football boots, red wellies, armfuls of coats, a frightening-looking plastic gun that made a lot of noise, a cricket bat and a tennis racquet both in the hall and on the front step of my humble abode. Clearly a sporty family. They also rigged up a pair of net curtains at the front window, something I’d always managed to do without until that point.

My gaff, for just one afternoon, was going to be lived in by one of the three stars of the show – Philippa Dunne (who plays the put-upon Anne), the kindest of the triumvirate of leading women. She is always lending a hand in one way or another. Apparently, in this series, she runs a voluntary maths class and a young lad was being dropped off by his dad for extra tuition. That was to be the scene.

At 1.45pm two more men with a health and safety remit arrived to check the surroundings. The child actor had to be allotted two ‘safe’ locations for those times when he wasn’t filming and the men pinned notices on certain doors, warning adults not to enter. The boy’s father also attended as extra security.

The film crew were simultaneously using the interior of the big pink house in Avenue Road for another scene. This one featured Lucy Punch, who I caught a glimpse of munching a sandwich in between takes. I noticed that her long, blonde tresses were covered by a plastic bag in order to protect her from the rain. When the two locations were taken together, there must have been nigh on 60 people involved, inside and out.

About 2.30pm the crowds descended on number 67. Everyone was disarmingly polite. The director Holly Walsh apologised for taking over my house and asked if she could get me a cup of tea or a chair to sit on. I was content to watch from the pavement on the far side of Chestnut Avenue in order to get a panoramic view of proceedings. Orders were barked from inside the house, then down a chain of command through the porch and out into the street. It seemed to be running like clockwork. Except for the time when I mistakenly drifted into shot and was asked to move out of the way. And filming temporarily ceased when mothers and their kids from Godwin School drifted past on their way home, wondering what was going on.

The afternoon became cold and I asked if I could go back indoors. The cry went up: “stop filming – owner returning to house”. I have never seen my front room so full – cameras, monitors, black screens, reflectors, sound engineers, runners, security guards, people brandishing clapperboards, a producer, an assistant producer, a director and an assistant director. Holly Walsh – the Holly Walsh –was sitting directing in the armchair in which I usually sat watching Spurs tumble to yet another defeat on the box. And then there were the thrilling cries of “camera roll”, “action” and “cut”.

Meanwhile, my kitchen had turned into the make-up room. Actors were ranged in front of the table poring over their scripts as make-up artists tried to dab at their upturned faces with cotton pads. I offered Philippa a cup of tea. “Better not,” she replied. “Might spill it on my coat. By the way, you’ve got a lovely house. It has a special feel to it. Easily the nicest one we’ve been in.” Well, thank you, Philippa. I bet you say that to all the owners!

Then the front door bell started ringing – again and again. Shooting had started. On the doorstep Philippa said: “Welcome to the maths class.” The director told her she loved the way she’d said that. There was an animated conversation at the door between Philippa and the father of the student. After a brief contretemps, he turned and left, walking down the very short garden path. “For the love of God,” said Philippa under her breath. It was impossible to know if that was in the script or whether she was letting off some actorly steam. I look forward to seeing whether that sentence ends up on the cutting-room floor or whether it’ll be in the final version.

Once the director said: “I’d like you to look more annoyed.” That took a few more takes. And then there were the other re-takes. But the team was nearing the end. What I hadn’t known was that this was the very last afternoon of filming. The show was in the can. So, at the last cry of “cut”, director embraced actor and producer embraced deputy producer and everyone asserted that it had all been “wonderful”. It was a moment for the luvvies.

One by one, camera by camera, they walked out of the door. Holly thanked me and then there was a sudden and eerie silence. Martin turned up and apologised for my payment not having come through yet. A snarl-up in accounts, he said. He’d see to it. And, indeed, he did.

In addition, he promised to send a cleaner round on the Monday, despite me saying that the house was looking immaculate. “It’s something we always do,” he said. So, number 67 ended up looking cleaner than it had been before filming started. There remained the outstanding issue of the hedge. There was no way out of it: it was time to get the shears out. Now that the creatives had packed up and gone, it was the only type of cutting I’d be experiencing for a while.

My doorway is used for several scenes in episode three of Amandaland. The first scene appears 8 minutes and 54 seconds into the episode and a few times after that. The series started screening on BBC1 at 9pm on 5 February.

22/02/2024

Non-fiction writers! Step forward

The less elevated role that non-fiction plays compared to the glitzy world of fiction can be detected straightaway in its lumbering prefix ‘non’. The type of writing in which facts are paramount is described in terms of what it is not. Hardly a good start!

Biographers and historians like Hilary Mantel occasionally – and quite rightly -stand waving their blockbusters beneath the bright lights but, on the whole, it’s the creative writers of the imagination who steal the limelight.

But the mansion of literature has many rooms. And it’s in the sturdy basement that histories, journalism, biographies, autobiographies, memoirs, textbooks, instruction manuals and self-help books take up residence. Not forgetting reference works, criticism, opinion pieces, essays, blogs, promotional writing, science books and documentaries, and countless other spin-offs. It’s these genres, with their (hopefully) unstinting dedication to unearthing reality’s truths, that are the foundation for the more creative endeavours going on in the rest of the house. It’s here that objectivity, based on historical, scientific and empirical evidence, is supposed to reign supreme.

A good non-fiction writer will write into these existing genres so that the work is placed within its category. Readers can then easily locate it and it makes sales and marketing a whole lot easier. This, I would argue, takes quite a bit of humility: one is just a cog in an information machine.

However, in recent years, non-fiction has unwittingly assumed a new, vital role. It has become an essential guardian of the truth. With fake news, AI and social media conspiracy theories staring us in the face, careful, honest telling of how it really is has never been so important. We need good non-fiction writers of prose like never before. Donald Trump won’t agree with me of course, which only serves to strengthen my argument.

So, what is required to produce good non-fiction? I’m going to divide the answer into three broad sections: research, writing and editing.

Research

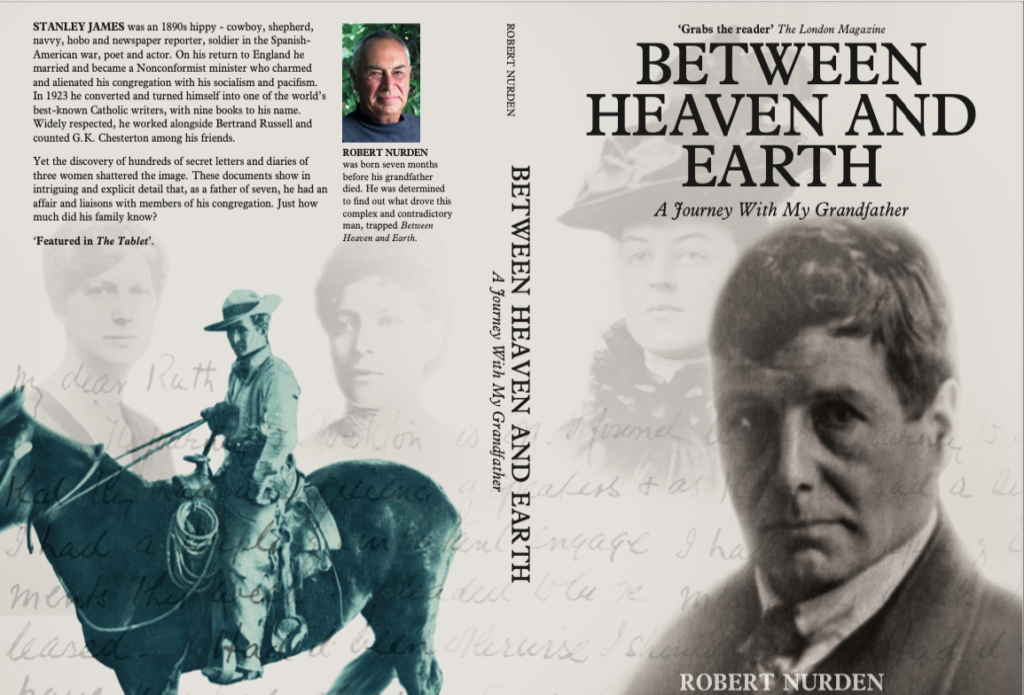

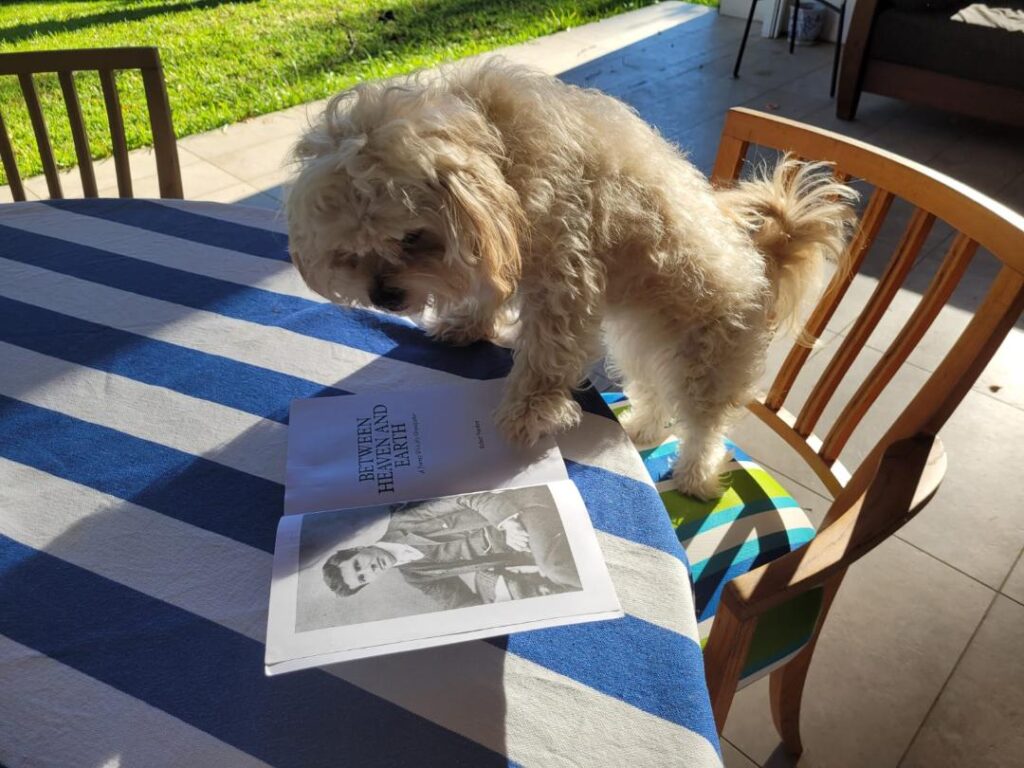

Watertight research is all-important, as I quickly learnt when writing ‘Between Heaven and Earth’, my biography of my grandfather. I was alerted to hitherto unknown aspects of his life in a book of early 20th century social history by an American historian. In just one and a half pages the writer managed to make 10 errors of fact. On meeting him later, he admitted he’d invented things in order to spice up the narrative. ‘I never thought I’d meet his grandson,’ he confessed. Moral of the tale? Just because something is written by an academic doesn’t mean it’s correct.’

This is echoed by Peter Williams, co-author of ‘Forest Gate: a short, illustrated history’. ‘Don’t publish things unless you are sure they are right. And always state your sources as it is so annoying for readers years later if you don’t say where you sourced things.’ And primary sources are gold dust to the researcher.

But it is also important to know when to stop. You shouldn’t include everything you find out. Every snippet of the subject you are passionate about may engage you but your readers won’t necessarily agree.

Writing

It may seem an obvious thing to say but you should be clear about why you’re writing your book. It may be that you’re sharing a passion, imparting knowledge, instructing, telling a story or even fulfilling a commission that you’re lukewarm about! Each of these aims will fit an established genre and a style that suits the material. Writing quality non-fiction requires planning and attention to structure, whether that be chronological in the case of history and biography, step-by-step progression in books of instruction or logical, narrative flow in memoir.

Everyone has their own way of writing but organisation of material is essential. What is the arc of the book? One can use the established narrative techniques that fiction uses – setting up a conundrum, followed by conflict and a resolution – except that this is likely to be argued intellectually rather than treated metaphorically or dramatically.

Set the scene and give context and don’t be afraid of employing the five senses. Establish which person you are going to use – first, second or third – and basically stick to it except when switching to another person aids understanding. Use the active voice whenever possible because it creates more interest.

‘The passive can be boring,’ says Pushpinder Khaneka, author of ‘Read the World’. ‘You need to vary it. Be careful not to let the writing become too prosaic. Keep it lively.’ Good non-fiction still tells a story, even if it’s on a topic like business or science. Dialogue adds life, too.

Yet the passive is a vital tool in explaining process and is used extensively in manuals and textbooks. It works when the reliability of the imparted information outweighs any entertainment value. As always, it’s a balance.

Everyone is different and obviously there’s no right or wrong way to construct a piece of writing. Some will strongly recommend finishing the research before putting pen to paper. I broke the rules in this regard with my biography. When I unearthed some shocking secrets about my grandfather it turned my book on its head and it became a different beast. But, as I was also a character in the narrative, I was able to exploit this unforeseen drama.

Notes are your armoury at this stage. These jottings should eventually morph into the beginnings of a structure. The narrative will have chapter headings, sub-headings and sub-points. A family tree-type diagram or a mind map may assist in seeing the overall shape. Then you have to decide the order in which the different sections appear. Chopping and changing is a natural part of the process.

When I turned to writing books, I found it impossible to throw off what I’d learnt in my years as a journalist. And, contrary to what some people may regard as literature’s Wild West, writing for the media is incredibly disciplined and controlled, not least as far as technique is concerned. There is always an editor sitting on my shoulder, checking everything I write.

My degree in English literature meant that the sentences I wrote for my first local rag, the ‘East Grinstead Observer’ (a tabloid), were too long. My editor called me in and told me that the absolute top limit for the number of words in a sentence was 25 but I should aim for 18 on average. And they should be simple. Avoid jargon: just because you use specialist language doesn’t mean anyone else will understand it. And, he said, never expect anyone to read a sentence twice; they should get it first time.

If only it was all that simple. In reality, the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction are continually blurred, especially with biography. ‘If we think of truth as something of granite-like solidity and of personality as something of rainbow-like intangibility and reflect that the aim of biography is to weld these two into one seamless whole, we shall admit that the problem is a stiff one and that we need not wonder if biographers, for the most part failed to solve it.’ So says Virginia Woolf.

One modern author who embraces the world of what is known as faction is Richard C. McNeff. ‘My Aleister Crowley spy series operates in a hybrid realm between fact and fiction, exploring the tantalising might-have-beens of real events and lives. Plausibility is vital, however. Contrast ‘The Crown’, widely derided for demonstrable falsehoods, with ‘Mr Bates vs the Post Office’, whose honesty produced such a heartening response.’ Rules are there for a purpose. But bending them may turn a competent piece of work into a masterpiece. Or, equally, a disaster. As ever, it’s whatever works best.

Editing

However skilled the writer, careful proof reading and editing are required. The first round should be done by the author and cutting extraneous material is a central part of this. Historian Mark Gorman describes himself as ruthless in this regard, having cut the manuscript of ‘Saving the People’s Forest’ from 100,000 words to 60,000. ‘It’s a very bracing exercise,’ he comments.

Editing by another pair of eyes is just as important. ‘A good editor can pick up on inconsistencies of style,’ said John Walker, author of ‘Out of Sight, Out of Mind’, the history of a notorious London workhouse. ‘I found my editor on Reedsy and she brought fresh vision and picked up things I hadn’t because I was too close to my material.’

In our world of echo chambers, cancel culture and political polarisation, reasonableness is often left stranded, mute and impotent. Good non-fiction writers can step in – indeed they must step in – and occupy that vacuum, filling the space with reliability and balance. Oh yes, and good old facts. Remember those?

30/01/2024

Venal Vennells Vanquished

Phil cradled his pint of Marston’s Pedigree and looked me in the eye. ‘Yes, Paula Vennells used to come in the Swan. But I never saw her – or her husband – buy a round. We never liked her.’ There was a twinkle in Phil’s eye, so I didn’t rush to write down what he’d said. ‘That’s a complete lie,’ he confirmed. ‘But who cares? She didn’t. Fucking cow. How dare she – a Church of England minister into the bargain – ruin the lives of hundreds of sub-postmasters just because she wanted to protect the good name of the Post Office?’ Usually, when a disgraced celebrity is hauled over the coals by the media, a feature writer will point to one redeeming feature that the perpetrator possesses: the ‘but’ or the ‘although’ of the piece, for the sake of balance.

But with Vennells none is to be found, at least not in the eyes of news editors. The disgraced CEO of the Post Office, who oversaw the malicious prosecution of hundreds of innocent sub-postmasters, is rightly seen as a hypocrite and a liar.

This utter condemnation fascinates me. The anger and bile that the scandal has given rise to fired me up. What was it about this case that got under the skin of the British public in the way that, for example, the MPs’ expenses scandal of a few years ago didn’t quite to the same extent? For want of anything else to do, I got in the car and drove up the M1 to Bromham in Bedfordshire to spend an afternoon in her village.

I told myself that later – if I ended up writing something about my visit – I would not feel the customary caution and need for fairness. This bitch took the biscuit and a true response to this case (the greatest miscarriage of justice in British legal history) was boundless outrage. I wouldn’t have to weigh my words carefully. Three cars were parked ostentatiously on the verge outside Vennells’s 16th century £2m pile, complete with picturesque pond to the front. They belonged to snappers waiting for her to emerge on to Box End Road. But the blinds were down and the curtains drawn. I was told later that the previous weekend she’d done a runner, taking her beloved motor boat, previously parked in the front garden, with her. No one in the village knew where she and her businessman husband John had gone.

Not that any villagers, apart from the vicar, had ever had anything much to do with her. Even though she was high-profile in the national media, locally she kept herself to herself, apart from getting involved in church business.

Next stop the local post office. ‘Hi, I’m a journalist and I’m sure you know why I’m here.’

The tall postmaster was bent over his cramped work area. He smiled knowingly but said nothing.

‘I wanted to ask you,’ I started breezily, ‘whether Paula Vennells came in here to buy stamps.’ I didn’t bother to shape my phrases carefully in order to elicit the most revealing answers. A liberated reporter. I was feeling strangely gung-ho and euphoric.

‘Yes,’ she did,’ he blurted out. Then, without a pause. ‘But I’m not supposed to talk to you.’

‘Did she pay by cash or card?’ I pursued.

‘Sorry. Stum.’

‘Is there anything I can do to make you talk to me?’ I went on.

‘No, nothing. Unless you pay me £1m.’ It was my turn to say ‘sorry’. Shame more people in the Post Office hadn’t used that word, too. I drove to St Owen’s Church, where the dog-collared Vennells had served as a minister after being ordained in 2006. She stepped down when the scandal broke in 2021. However, officially she remains an ordained priest and has been supported by her diocese (not God in this case, I am led to believe). A spokesman for the Bishop of St Albans said it would not be right to judge Ms Vennells until all the facts are known in the wake of an ongoing public inquiry. The spokesman said: ‘It [the television drama, Mr Bates vs The Post Office] is a bit like The Crown where it diverges from actual fact into TV.’

In addition, Vennells came close to being appointed the Bishop of London when she was on the shortlist of three for the job and was even thought to have had the backing of the Archbishop of Canterbury. She was interviewed for the third most senior job in the Church of England but was ultimately unsuccessful. And I learned that, incredibly, this scumbag had been a member of the Church of England’s ethical investment advisory group before her membership was terminated in 2021. St Owen’s Church was locked but the porch area was open. On its walls were pinned numerous notices about local events. Scores of names of organisers of this and that committee were plastered all over the noticeboards but any reference to Vennells was conspicuous by its absence. Likewise, the January 2024 edition of the Church News made no mention of putrid Paula. A sheet listing the forthcoming week’s activities quoted Psalm 133 in passing: ‘How good and pleasant it is when God’s people live together in unity!’ I recalled one of her former employees reflecting on what it was like working for this piece of excrement. ‘She was undeniably dim,’ he said. ‘Promoted above her talents.’ Personally, I would never trust anyone who uses the word ‘surface’ as a verb. It’s an indication of a mediocre mind, fashioned by management-speak after attending too many training courses. Here’s the quote in question, taken from the Post Office inquiry: ‘If there had been any miscarriages of justice, it would have been really important to me in the Post Office that we actually surface those. And as the investigations have gone through so far, we’ve had no evidence of that. And, as you all know, we’re bound by the Disclosure Act to make known anything that we have come across that might contribute to that.’

As I turned away from the church and made my way towards the car, I saw a middle-aged woman walking on her own through the car-park. Nothing ventured. Nothing gained.

‘Did you know Paula Vennells?’ I asked.

‘Oh, I suppose you’re a snooping journalist,’ she countered.

‘Exactly.’

She smiled. ‘No, I didn’t, thank goodness. I didn’t even know she lived in the village until someone told me. But I signed the petition demanding that she hand back her CBE. Disgraceful.’ We exchanged excoriating views about conglomerates and how the little people always suffered. I detected a twang of a foreign accent and she proffered the fact that she was Dutch. Living in an alien land.

‘It doesn’t surprise me that Vennells lived in Bedfordshire,’ she said. ‘I’ve been living here for 15 years and I still don’t really know anyone. They are particularly unfriendly. I go to Norfolk on a regular basis, just so that I can chat to people … bus drivers, shop-keepers, you know. Bedfordshire is a strange county, with a history of brick-making for other places as well as being a cabbage production line. This is market-garden city.’ She paused. ‘No, sorry, I can’t help you. There’s a man cutting down a tree over there. He may know something.’ On another day her diatribe may have persuaded me to stay. Here was a lonely and sad woman. And maybe she had a point about the strangeness of Beds. But I made my excuses and left. At the Mill Café the manageress didn’t know Vennells either. In fact, she was glad that she didn’t. ‘She never came in here. I’m afraid I can’t tell you that she walked out without settloing her bill. Nothing like that. How’s the soup?’

As I left the café, the manageress called out to me. ‘Actually, there was one thing I forgot to mention. You may know this already. I was looking her up on the internet and the date she joined the Post Office as CEO was significant, I’d say.’

‘Oh yes. What was the date?’

‘The first of April.’

I rest my case.

4/11/2023

Truth, Like Fire, Purifies Everything

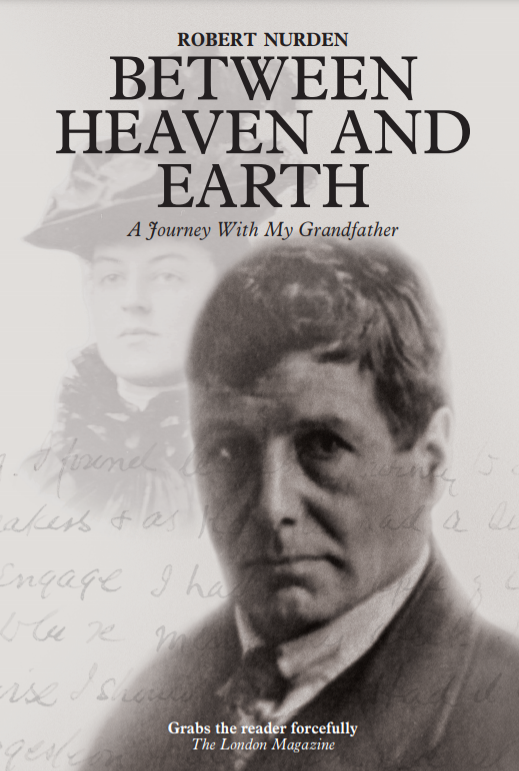

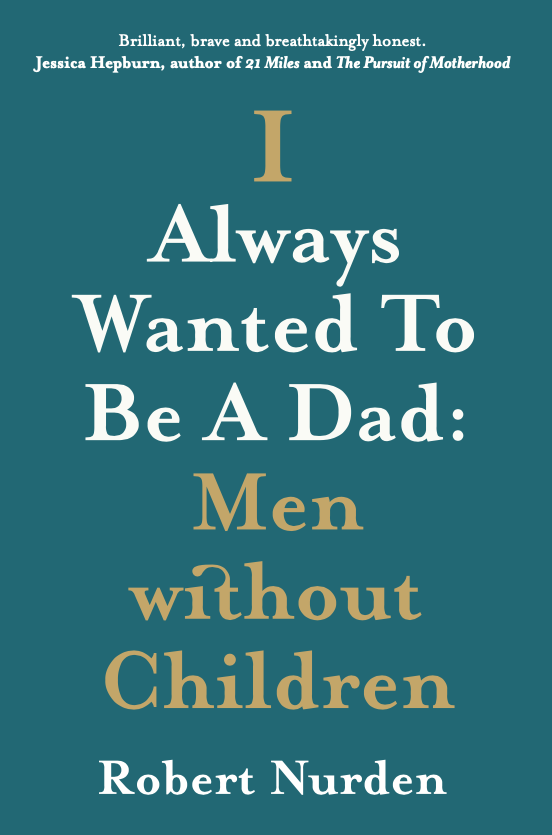

I’ve got two non-fiction books in the bag now. My first one – Between Heaven and Earth: A Journey with my Grandfather – came out in November 2021 and my second one – I Always Wanted To Be A Dad: Men Without Children – in August this year. On the face of it, two very different, unconnected projects, apart from the fact that I wrote them both.

Nevertheless, I asked myself, wasn’t there some kind of link thematically. So, I delved deeper into my own words to see if the books weren’t somehow closer than I first imagined.

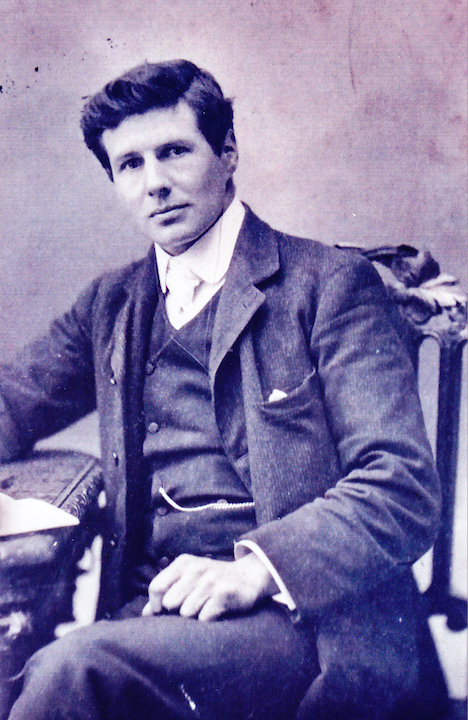

My maverick grandad Stanley James – cowboy, adventurer, soldier, priest, communist, philanderer, pacificist and Catholic convert – is the subject of my first work. I’m a bit loath to call it a biography because in it I have dramatized my own research; indeed, I appear in it.

You see, my grandfather died seven months after I was born so I don’t remember him and certainly didn’t know him. But, despite the fact that he had seven children, one of whom was my mother, and that he was a highly regarded writer, the family hardly ever mentioned him. By the time I came to write the book of his life, all his children – my mother, uncles and aunts – had passed away. It was too late to find out from them if something was being hushed up.

All I had to go on was his books, including two autobiographies, and thousands of articles and letters. If I hadn’t had those, I couldn’t have written the book. But gaping questions remained unanswered. Just why had the family been so steadfastly silent?

It fell to me to document his life for the first time. Gradually the curtains were drawn back and I was taken to some unexpected places. Clearly, there were secrets to unlock. Throughout his literary output, it emerged – after some painstaking research (by the way, I enjoyed the investigation as much as the writing) – that he had frequently embellished the truth, invented things, covered things up and even lied. Enough baggage, then, for the family to draw a veil over.

My sleuthing took me to Canada, as well as to archives all over Britain, and eventually I was able to piece together a more authentic picture. The quiet, reflective family record that I had anticipated writing had turned into a piece of investigative journalism. Despite the relative success I had in this regard, I know I still haven’t got to the bottom of his enigmatic life.

My second book, I Always Wanted To Be A Dad: Men Without Children, is all about me. The title faithfully describes the content. In fact, a seam of no-holds-barred transparency runs through the 28,000-word work. In the intensely personal chapters I unravel the pain and regret I felt when I didn’t become the father I expected and longed to be.

I have never been so revealing in anything I have written, even in those private adolescent jottings that no one else has ever seen. Maybe it’s something to do with the fact that I am towards the end of my life and there is nothing to lose in being brazenly open. The one aspect that reviewers have focused on is the book’s ‘breathtaking and brutal honesty’.

So, one book is a largely objective treatment of my grandfather’s life in the pursuit of the true facts of his life. The other is a bleak, navel-gazing act of self-revelation – full of hurt – until, finally, arcing towards a kind of acceptance.

The French author Emile Zola once responded to criticism that some of the events contained in his novel Germinal were too stark by saying; ‘Truth, like fire, purifies everything.’ As I recalled this quote, I had a eureka moment. These words suddenly provided a clue to what I was searching for. It had taken me a while to realise that the common thread running through my very different books was an obsessive, psychological need in me to be glaringly honest, whatever the cost. The first was a ruthless and honest assessment of my grandfather; the second a hard-hitting examination of male childlessness, combined with a focus that didn’t flinch from the mistakes of my own life which had contributed to this state of affairs. I had needed to wait for my words about male childlessness in I Always Wanted To Be A Dad to settle before the broader theme became apparent.

I am no psychologist so I can only speculate as to why I was driven to peel back the layers of pretence and lay before the reader deeply uncomfortable truths. More than is usually the case among writers of biography or memoir. It certainly brought a sense of power. But, more significantly, I would hazard a guess that I saw it as my mission to expose the hypocrisy behind many aspects of my childhood; certainly, a buttoned-up, claustrophobic English reticence. It was, perhaps, my act of revenge.

One final thought: I would argue that the very act of being searingly honest is in itself life-affirming, almost irrespective of the content. My two books are experiments in trying to achieve the highest possible level of honesty on the page. The works are vehicles for my own catharsis, and in this sense they were successful. One happens to be about my grandfather and his indiscretions; the other about my childlessness.

2/1/2023

Something There Is That Doesn't Love A Wall

“No one knows their neighbours in London. It’s such an unfriendly place, so impersonal.” You know the kind of thing they say. We’ve heard it all before.

My experience this Christmas has made me wonder if these negative mantras are fair to England’s capital city. No two ways about it, my partner Sue and I have been swamped by kindness from people living nearby.

For weeks now Pete, our local garage mechanic, has been leaving bags of chopped wood outside the front door, which are perfect for our open fire. In his eighties, most days during his lunchbreak from his place of work underneath the railway arches, he wanders up and down our road. Cars are his passion and he gets pleasure from casting his eye over anything parked in our street.

After he’d serviced Sue’s Yaris, he did some extra bits and pieces quite beyond the servicing remit. He then proffered advice such as “make sure you remove tempting objects from the seats when you lock up”. All delivered from behind an abundant beard and with a softly spoken voice that belied a deceptively gruff demeanour.

We used to greet him on the many times our paths crossed. Often, he stopped and asked how the Yaris was running. Fine, we said, which it was. Starts every time, even after night-time temperatures of minus five. On one occasion I let it drop into the conversation that we had a real fire in our front room on which we burnt coal and wood. He remembered this. The next day a bag of recently chopped wood appeared on our doorstep. Then another and another. The next time I saw him delivering a bag, and I went out to talk to him. After thanking him for his quite unnecessary acts of kindness, I asked him what he wanted for it. “Nothing,” he said. “It gives me something to do at the weekend. I’m doing some for my boss so I thought I’d do some for you, too.” I gave him a bottle of Laphroaig for Christmas.

I needed to buy a car and he offered his free advice. “Get another Yaris,” he said. “Toyotas are reliable and so are Hyundai.” When I went to a dealer in Romford there was a Hyundai with just 25,000 miles on the clock so I bought it. It runs really well – and it starts every time. Thanks, Pete.

On Christmas Day itself we were lazy and we still hadn’t cooked or eaten much by six in the evening. Sue is restricted as to what she can eat and it was always going to be a simple meal. Then there was a knock on the door and there were our neighbours – Liudmyla from Ukraine and Marius from Lithuania – standing in the dark of the porch. They were holding out something on a plate which turned out to be part of a joint of beef surrounded by sweet-smelling roasted veg. There was also a bowl of potato salad and some wafer biscuits on offer. Oh yes, and a packet of sweets. “Happy Christmas,” they chorused. “We are Catholics in our countries and this is how we celebrate. The wafers are usually for Eucharist service.”

How did they know that we were tired out and the last thing we wanted to do was cook a meal? Now we had one – still hot and ready to eat. We had nothing for them. But we took it in and sat down to eat it. It was a lovely piece of beef. I, for one, was overwhelmed by their generosity. They knew Sue was ill and this was their response.

Flowers and a card from Danny and Katie, a homemade card from Rod over the road and a card and a box of chocolates from our Polish cleaner. Just before Christmas Sue contracted Covid and was still testing positive on the day itself. She was drained of energy, the virus coming on top of the chemotherapy treatment she was having for breast cancer. The festival had taken up residence elsewhere. But our neighbours lifted our spirits, even more so because their kindness was so unexpected. What’s more, it was appropriate, providing the staples of food and warmth.

I reflected on our neighbourly Christmas connections. And I thought back to the snatches of inconsequential greetings over the garden fence we’d had with them over the previous three years or so. They seemed nothing at the time, sometimes irritating even in their superficiality. But if we hadn’t given them the time of the day, the omission would probably have engendered feelings of resentment or brooding hostility, on both sides. It was almost as if the regularity of those meaningless exchanges had its own positive momentum. The human being is such a dynamic, energetic, complex bundle of sensations that it connects even when it doesn’t particularly want to.

This brotherly and sisterly love also made me think of Robert Frost’s great lines: “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall, That wants it down.” Like he so often does, with those deceptively simple Anglo-Saxon words, Frost hits upon a universal home truth, a truth that applies to London just as much as it does to, well, anywhere.

18/8/22

Can Your Brain Take the Strain?

After many months of not travelling very far from home, the past week or so has seen me taking train and bus journeys on a grand scale. And what I encountered was nothing less than a travel labyrinth of mind-boggling complexity. So complex in fact that I wonder if I any longer have the skills to cope with today’s Kafkaesque transport systems.

On one occasion, when I was caught in a particularly severe maelstrom of mix-ups, I even wondered if universities should offer travel degrees; getting about on trains and buses now requires top-notch powers of analysis. The old British Rail slogan: “Let the train take the strain” has been supplanted by “Can your brain take the strain?”

The vagaries are caused, I contend, by three different factors: digitalisation, which, with its own twisted binary logic, can create unforeseen errors and more confusion; excessive privatisation; and a shortage of staff, which in turn can provide poor customer service and unreliable – even contradictory – information. All these three, in 2022, are conspiring to produce a perfect transport storm.

My first trip was with East Midlands Railway (EMR) from St Pancras to Cromford in Derbyshire, with a change at Derby. I boarded the 15.02 and waited. It wasn’t until 15.25 that we left London, the reason being that there was no driver available. He was on a train that was coming in from Sheffield but which had been delayed. Passengers were told that there was no replacement driver. “We can’t get the staff,” said an official.

In addition, overnight “cables were stolen from the line near Wellingborough”, which meant the train had to slow down. Then there was the “debris” on the overhead power cables further up the line. This meant that I arrived in Derby 20 minutes late and I missed my connection. My friends were left waiting for an hour before I arrived on the next train at 6pm instead of 5pm.

On the way back, two days later, I looked at my return EMR ticket from Cromford to London and saw the time 15.09 printed on it, assuming that was the departure time from Cromford. I told my friends and we allowed plenty of time for them to drive me to the station. But, knowing the local train times, a little later they questioned it. I double-checked and saw that 15.09 was in fact the departure time from Derby. We made a lightning dash in the car but missed the train by two minutes. We then drove helter-skelter for Derby and caught the connecting train with four minutes to spare. Thank you, John! Partly my fault, of course, for not consulting more closely, but why was 15.09 printed on the ticket (which I didn’t really need to know) while I most definitely did need to know that the train left Cromford at 14.20.

A few days later I travelled from King’s Cross to Montrose in Scotland – and this is where the fun really started. My digital LNER ticket told me that all the reserved seats on the 10am train had been taken and warned me that I may have to stand for the whole of the six-hour, 21-minute journey. But there were, it told me, some unreserved seats in coach C. I resolved to arrive at the station early to grab one.

Before the platform was announced, I consulted an official. Well, he said, after consulting his iPad, your train is already in on platform five but it’s locked. However, if you head up the platform to where coach C is you can be first in the queue when the doors open. Invaluable insider information. Alertness: part of the new skill-set needed for negotiating today’s unpredictable transport system.

Well, coach C was open and I found a forward-facing window seat with a table and a green light above it which, I presumed, meant that it was available. Long gone are the days when a coupon placed on top of a seat back told you that that place was reserved and to which journey the reservation applied. Lights do everything now. By the way, scores of people were left standing the length and breadth of the train.

I broke the journey at Arbroath in order to indulge in my first Arbroath smokie – a smoked herring and a local delicacy: and a fine thing it was. All that remained that day was a one-hour bus journey to my final destination – Brechin – via Montrose. I reckoned I’d get to see the lie of the land through the windows of a slow bus better than through those of a train. It was true but I made a mistake in thinking that I could use the freedom pass that had been issued in London to get free travel on buses throughout Britain: it was not valid in Scotland.

The next day I had an appointment at 10am in Forfar, a town 13 miles from Brechin. The Stagecoach website told me that the 21 would take me there. While I was waiting at the bus stop, the driver of another bus, temporarily parked up in the bay, wandered over and asked if I was heading for Forfar. I told him I was. He checked his iPad and informed me that the service had been cancelled and so had the next one.

So many drivers – he was one of them – had resigned from Stagecoach because the company allegedly treated its employees so badly. He had jumped ship and signed up with Angus Council and now drove their shuttle bus between outlying villages. Because of the daily cancellations he had taken to ferrying stranded passengers like me part of the way to Forfar and dropping them at Friockheim where they could catch another bus to their destination. And it was free! Naturally, I took up the offer. It was another instance of how today’s traveller has to be ready for the unexpected. Could the freewheeling, unregulated days of chaotic 19th century travel be back with us I wondered.

Two days later my return trip beckoned. It meant taking the 21 bus from Brechin to Montrose where I would catch my return train to London. Knowing the unreliability of the service, I caught a bus that was ridiculously early for my train. At the train station I failed to press the stop button, wrongly assuming that the bus would automatically halt at such a major stop. The bus drove past the stop so I hastily pressed the button, only to be harangued by the driver for not doing it sufficiently early. Oh dear!

While waiting at the station, I overheard a conversation between a passenger and a railway official. It was all about the reference number for her ticket which she thought she had but it turned out to be the wrong one: it was a booking reference not a ticket reference. She was exasperated and her train was approaching. In the end she ignored the strictures of the official and boarded the train. An example of over-complicated, digitalised ticketing regulations which only serve to obfuscate what should be a simple process. So often, there are two parallel information streams: one digital and the other human and invariably they do not marry up. I hope she made her destination.

My train arrived dead on time. My ticket said I was in seat 74 in coach H but once in the carriage my reserved journey for Montrose to King’s Cross had been placed in seat 71. People were already sitting in both seat 74 and seat 71 and refused to move. I sat in an unoccupied seat and waited for the guard, who hopefully would sort out the mess.

Exasperated, he said: “Oh no! Not again! Crossed wires. We’re getting this all the time now.” I had been allotted the wrong seat because digital had not talked to human. However, luckily, my illuminated Montrose to King’s Cross seat was now vacant so he encouraged me to “move there and stay there”.

But at Edinburgh Waverley a woman came into the carriage and claimed I was in her seat. She, too, had been allotted the wrong number by the system. Happily, not every seat had been taken and she was able to take an unreserved seat for the whole of her journey to London.

Coach H was billed as a quiet carriage, which I had deliberately chosen. Actually, to be strictly accurate, LNER had sneakily called it a “Quieter Carriage” which kind of gets it off the hook. But whichever word one uses, the description was a misnomer, given the continuous noise I encountered for much of the journey. Not mobile phone conversations, as is usually the case. A party of raucous schoolgirls were screaming, playing cards and thumping their winning snap hands loudly onto the table. Later I experienced the cacophony of plastic bottles being squashed by hand and babies crying incessantly. Quiet(er) carriage? Huh!

At the barrier at King’s Cross, I was required to dig out my digital ticket from my phone and pass it over the electronic reader. Damned if I could find it. Instead, I waited for a couple to pass through the gates and slipped in behind them. They were grumbling about technology and we shared a laugh about so-called progress.

On the Tube (it was quiet – no one was playing cards or squashing plastic bottles), I reflected on my recent transport Armageddon and its causes: the triple whammy of excessive and inflexible digitalisation; mass privatisation of rail and bus companies; and a shortage of labour. All of which combine and lead to a snarl-up in the passenger’s head, not just on track and road.

Perhaps I should have used the car after all.

22/6/22

Ode to a Blackcap

For some time now my partner and I have bemoaned the fact that our neighbours’ garden has become unkempt and overgrown. It shouldn’t matter and it doesn’t really but nasty, unwanted weeds have taken to crawling under the fence at night to take root in our border. Then there’s the wall of ivy that has scaled the fence and is slowly smothering our climbing plants.

In what can only be described as an act of small-minded, nimbyish, urbanised revenge, we gathered up all the snails and slugs that these incursions have produced and lobbed them back over the fence. At first, we did it under cover of darkness. Then we grew bold and showered the offending plot with a regular supply of crustaceans in broad daylight.

Our neighbours are such indoor creatures that even if they had seen us out of the back window, they wouldn’t have cottoned on to what was happening. Their seeming sole use of their garden is as a smoking room after 11pm. As they scream down their phones, cigarette in hand, the issue of noise pollution is added to an already toxic cocktail. At the end of the day, though, we are probably the losers: all the slugs and snails will do is simply return from whence they came: our garden.

Yesterday I was in the garden enjoying a book in the lovely weather. I was also nursing Covid, having gone down with the bug a few days previously. I was over the worst of the disease and I felt fine, except for two things: my sense of taste and smell had disappeared and I was still testing positive. It meant that our holiday in Portugal had fallen through. And I had to self-isolate. The only thing to do was sit, read and wait.

We have some bird feeders and at this time of year they are overloaded with sparrows and starlings. The fledglings can also be seen lined up in rows on the fence waiting to be fed by their parents. We love to watch them as gradually they gain in strength and confidence and swoop to the feeders themselves where they squabble and jostle to get to the front of the queue.

We are also visited by a pair of pigeons which are massive and land like jumbo jets with their massive undercarriages on the fence, sending it rocking. Then, at quiet times at the beginning of the day, robins appear bobbing along the path vacuuming up the dropped seeds. Great tits and blue tits, too, and a squawking magpie on top of the tall fir tree. That just about completes the picture. We have to admit that no exotic species visit our al fresco dining table but that’s the way it is these days with bird populations declining so rapidly. We are just glad to be able to host something.

As I sat reading, ever so imperceptibly, snatches of bird song wormed their way into my consciousness, gently pushing aside my focus on the storyline of my book. It was a good novel so the reason for the distraction had to be good, too. It was. The sound grew louder and more insistent but that was probably my imagination as my mind quietly – and without complaint – distanced itself from the clutches of plot and character. Eventually I put the book down.

An unfamiliar, chattering, warbling song was drifting over the fence from our neighbours’ unruly garden. It came in bursts and lasted roughly three seconds. It rose and fell with lightning speed. There was something of the manual typewriter about it. Yet it was also a pretty, sweet sound like a flute in its higher register – and it entranced.

The song was coming from midway up a tree with dense foliage, so I couldn’t see the singer. All afternoon, it stayed hidden except for two occasions when I managed to spot it. The first time it was flying, darting with a slightly swooping trajectory, from one safe haven to another. The second time it boldly perched on the branch of a tree without foliage in full view. It sang its little heart out and I looked and listened, transported. On its bare branch, I could just about make out its black head, which probably meant that it was a male blackcap. The female has a brown head.

I listened for perhaps another half an hour before returning to my book. At the end of each chapter, I put down the book as my choral evensong was still flowing with mellifluous ease from the undergrowth. I phoned my partner, said nothing and let her listen. Then I phoned a friend.

Research that evening showed that the blackcap was nicknamed the “northern nightingale” or “mock nightingale”. It is classed as a warbler. Happily and rarely, its numbers are increasing in Britain, probably because of global warming. It used to migrate to warmer climes in the winter but since the 1960s some blackcaps have started overwintering here.

This, in turn, is having a bizarre knock-on effect on, would you believe it, mistletoe. For the birds who stay here, one of their favourite winter foods is this white-berried parasite. Apparently, they separate the berry from the seeds, which they smear over the branches of the host tree and this encourages growth. So, more mistletoe and, hopefully, more kissing at Christmas, too.

The blackcap is shy in every other way. Its plumage is mostly grey so looks don’t really come into it. And, like the nightingale, its fame rests on its song. And what a song that is.

Now we don’t mind our neighbours’ garden being overgrown. In fact, we prefer it that way. To be honest, we’re a little bit jealous because – without knowing it – the dense undergrowth in their garden is probably hosting a pair of blackcaps complete with nest, tiny mottled, grey eggs and, before too long, young chicks.

Oh yes, and this morning I finally tested negative for Covid, thanks perhaps – you never know – to the healing powers of my beautiful blackcap.

31/1/22

My Northern Star

One of the benefits of self-publishing, it is said, is the level of control authors have over their book. They can even design the cover. That last factor, instead of acting as an incentive, filled me with horror. It made me hark back to an experience I had as a sub-editor on the Independent on Sunday.

As a sub, ask me to design a page and my stomach turns, particularly if a deadline is looming. I was number two on the subs desk of the business section which meant that Matt, my superior, was normally on hand to design the front page. The business editor – a nervy chap at the best of times – invariably hovered, expecting perfection. One week, Matt handed me the job “to give me the experience”.

I don’t need to tell you that the best stories are always put on the front page, so it was doubly important to draw the right size shapes to accommodate the number of words for each story. This I abysmally failed to do, and the wrath of the irascible editor was incurred. Matt electronically grabbed my hazy maze of lines, redesigned the whole page at lightning speed with the production editor shouting from the other side of the newsroom, and saved the day. Lesson learned: I would never make a designer.

So, years later for my own book, I needed to find one. I went to Reedsy and invited people with non-fiction experience to respond. Adam, from Stockton-on-Tees, came back within the hour. Why so fast? Was he desperate for work? We quickly got into an online conversation and it transpired that he had a contract with publishers Thames & Hudson. He had plenty of work, but he also liked working on projects with indie authors.

I sent him some photos. “Good-looking chap your grandfather, wasn’t he?” he chirruped. “Make a great cover.” I warmed to this. After all, strong single images on covers within Adam’s portfolio had initially attracted me to his work.

I also sent him the synopsis and some more photos and I felt he “got” the book straightaway. We agreed a deal for him to design the cover and after a couple of days he delivered eight designs. There were many good shots of my grandfather but one in particular – one in which he resembles a Hollywood matinee idol – stood out for Adam and that went on the front and stayed there.

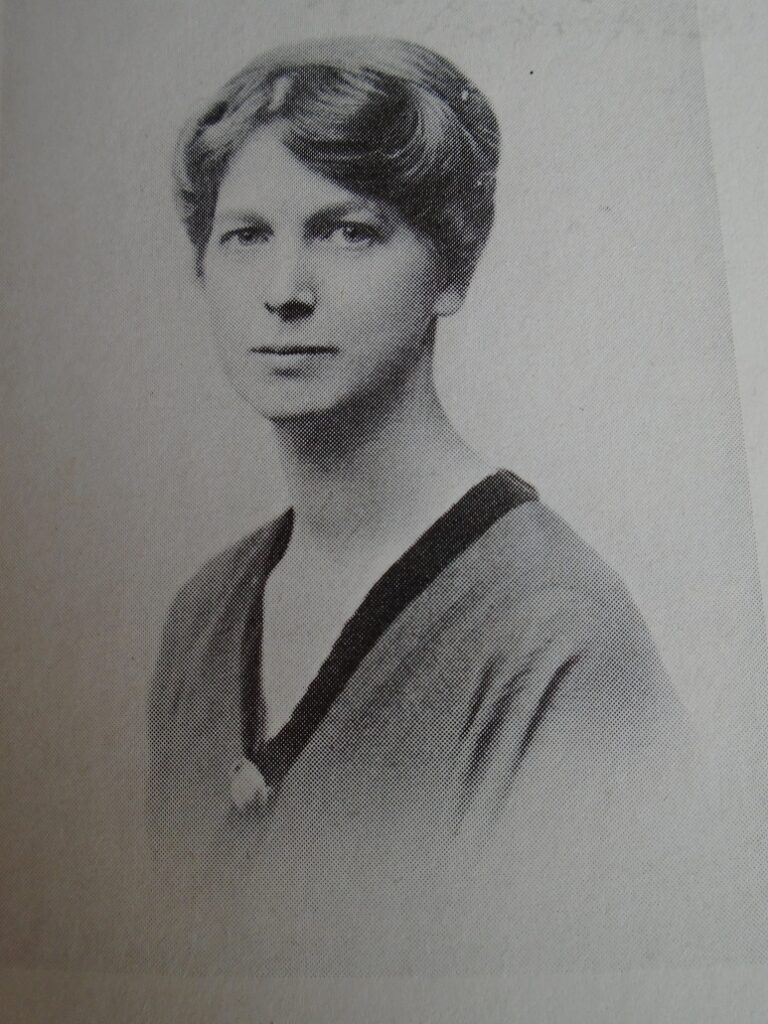

To soften the overtly masculine tone he put a shadowy portrait of my grandmother behind Stanley, but this wasn’t quite right because it reminded me – detrimentally – of that all-embracing maternal image that is Piero della Francesca’s Madonna della Misericordia. He tinkered with it and all was well. In the background he added the mysterious faces of two other women in my story, along with the haunting image of a real love letter. It worked beautifully. We were all but there. For the title’s typeface Adam suggested a retro style in order to capture a sense of the old journalism that my grandfather was involved in. No need to quibble over that – it was a stroke of genius.

He even anticipated potential problems with Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP), so flipped my name on the spine into a vertical format because having the name horizontally ran the risk of it bleeding onto the front or back if the printing process went wonky. With all these complexities coming to light, I was glad I’d shunned the DIY route.

It was an easy decision to let him loose on the interior, where Times New Roman was again the order of the day. In addition, he placed the words of the section headings in frames borrowed from the type of thing used in silent film placards. I had to choose the right photographs, ask a friend to turn all of them into 300 dpi, and then send them on; finally write and invariably rewrite the captions.

I had to quickly dismiss any thought that two or three proofs would be the end of it. We totted up eight proof versions. Because he was designing everything on a sophisticated Apple Mac machine, I couldn’t make the amendments and corrections myself. I had to compile lists and email them on to him. Eventually it was time to order print proofs. And just when I thought that the proofing process was complete, on reading through the pages of the book, I found a worrying number of errors: it is amazing how much more the eye sees on paper than it does on-screen.

We got there, of course. And now I have a lovely looking book. Nothing was too much trouble for my patient and long-suffering designer from the north.

24/1/22

Beware: Labyrinth Ahead

It’s not quite true to say that the challenges involved in self-publishing made me regret ever writing ‘Between Heaven and Earth: A Journey With My Grandfather’ – but almost. I lost count of the number of times I just wanted to send my manuscript off to a traditional publisher and have done with it.

I’m not going to pretend that it was a steep but positive learning curve, worth all the headaches and heartache. Nor am I going to be glib and say that if you persevere, you’ll get there in the end. Instead, I will issue a health warning: anyone setting out on the author’s indie route for the first time is almost destined to find it far worse than they imagined.

Before diving in, I discussed the issue with a couple of friends who knew a little about literary matters. They urged me to try the old-fashioned route before succumbing to the DIY approach. So, I tried to find a literary agent. Having scoured the Writers and Artists Yearbook online and picked those that dealt in non-fiction, I wrote to about 12 of them. I received replies from three, only one whose letter was a bespoke response – but still a no-no.

I also wrote direct to a number of publishers. Not so many, perhaps five. No reply at all from any of them. I cheered myself up by reasoning that it was all to do with Covid-19 and that under normal circumstances they would have been elbowing their way towards my book.

Now another search was required: this time for an editor. Luck was on my side. A good friend of mine, who was a successful self-publisher and who proudly claimed that his book sales were significantly boosting his pension pot, recommended Jen. Jen lived on a remote Greek island, but I caught up with her when she was in London and we agreed to go ahead. I needed a structural editor who would stand back and advise me on which parts of the book worked and which parts needed adjusting. This she did, but she tired towards the end when ‘the religious bits’ overwhelmed her. It cost me £750. No matter, she basically did a good job and I carried on where she left off and ruthlessly shaved off whole passages that were flabby and added nothing to the narrative. I also needed to reduce the size from a hulking great 123,000 words to something more like 100,000.

After the structural editing came the close, textual editing and here Jen recommended another editor friend of hers who lived in Fremantle, Australia. Ian was painstaking in his checking and did an excellent job. Cost: £400. He put me right on the most minuscule of things: for example, coming from a journalism background, I made my speech marks double inverted commas instead of single, which they are in books. Newspapers put all numbers above nine in digits – so 10, not ten. Which is how I wrote my numbers. The ever-meticulous Ian changed the lot to match publishing norms.

So, self-publishing it had to be. Now came the issue of who to go with. Amazon, IngramSpark, Lulu. Blurb, Smashwords? The list seemed endless and their websites all claimed to provide the universal answer to the stressed-out indie author’s problems. I had no way of knowing which would best suit my purposes. It was that dark labyrinth again. I sought help and advice, but I found that while some independent authors knew discrete areas of self-publishing well, no one could give me a much-needed overview.

Instinctively, I wanted to avoid the behemoth that is Amazon, but successful self-published authors pointed out the extraordinary extent of its distribution arms, tentacles which reached all corners of the world. As I wavered, I could feel its alluring tendrils encircling me and my book. Well, dear reader, I allowed this faceless 21st-century monster to have its evil way with me. One month on from publication day, I still don’t know if I did the right thing.

02/08/21

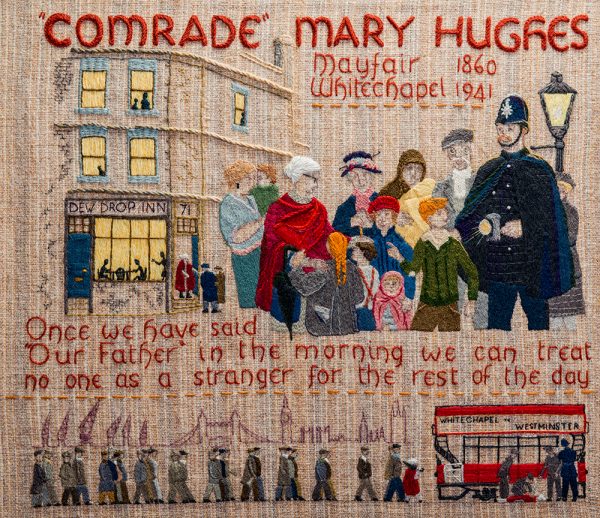

When Do-Gooders Do Badly

We’re back in the early years of the Twentieth Century in London’s East End. Imagine, if you will, four earnest-looking people sitting round a simple wooden table on which lie notes and coins, food and clothing. In one corner of the bare room, waiting for the ceremony to come to an end stands a group of London’s poorest.

What you are witnessing is the weekly prayer meeting of the Voluntary Poverty Movement, the centenary of whose launch falls this year. In 1921 a band of revolutionary Christians – more grandly known as the Brethren of the Common Table – met regularly in London’s Bow district to share with the needy what they thought was excess to their own needs. It was an initiative in which the rich sought to dispense with their wealth and make themselves poor.

Yet, as it played out over the next few months, this short-lived piece of pie-in-the-sky idealism constitutes one of the most hypocritical acts of do-gooding in the British charity sector.

All started well. Newspapers such as the Evening Standard, as well as many other English-speaking newspapers all over the world, covered the launch of this idealistic yet essentially practical take on Christianity. The Standard noted that the group were even prepared to “face exploitation” by less needy people claiming the handouts.

The leader of the Voluntary Poverty Movement was Muriel Lester, a rich heiress from Loughton in Essex, who with her sister Doris had been working to alleviate the conditions of the working-class in Bow for a number of years. She is best known for her friendship with Mahatma Gandhi, and it was she who hosted him on his visit to Britain in 1931.

Muriel told the Standard: “We welcome both saint and sinner, preacher and purloiner, dukes and dockers, clergy and convicts… We came into existence because we realised that it isn’t enough to give away money. We feel we have no right to possess it.”

The other three signatories were Rosa Hobhouse, Mary Hughes and the Rev Stanley James. They met in an old chapel where new premises were built later, the community centre that became known as Kingsley Hall, which was where Gandhi stayed.

But the four signatories didn’t practise what they preached. They did not “reshape their lives” as their newly taken vow of poverty stipulated they should. The press got on to these failings and lambasted the quartet for their hypocrisy.

Journalists realised that Muriel was relying on her sister Dorothy (who didn’t join the movement) for financial support. The recent death of their father Henry, a wealthy shipbuilder, had made them beneficiaries of his huge estate. Although Rosa’s husband Stephen had renounced his claims to his family’s Somerset estate, he and his wife set up a family trust which comfortably cushioned them from financial hardship.

Mary Hughes, who was the daughter of Thomas Hughes, the author of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, retained control over an inheritance which included several substantial properties in Buckinghamshire, although she did make these available as homes for the unemployed and “fallen women”. In reality, none of them had made any significant sacrifice.

Only one of them – the fourth signatory, the Rev Stanley James – had done so but the resulting burden fell not on him but on his wife and family. It is here that I must declare an interest: Stanley is my mother’s father and I learned of his involvement in Voluntary Poverty as a result of my research into his life for the biography I was writing of him, Between Heaven and Earth: A Journey with my Grandfather. At the time of his participation in this ill-fated enterprise, Jess, his wife (and my grandmother), and their seven children were themselves living out a life of poverty in a remote cottage in the Mendips.

Stanley, who was to write nine books and at the time was editor of the Crusader, a pacifist journal, wrote in his autobiography that conditions at the family cottage “were as primitive as those of a prairie shack, but no one seemed to mind”. This view was not shared by others. There was no running water, so they had to collect it from a nearby spring; and they had to live on what they could grow in the garden. The seven children were forced to share beds and sleep top to tail. Jess’s life was one of unending drudgery and hardship.

There is no evidence that my grandmother knew that her husband was re-directing the little money they had to the poor of the East End. Stanley never once mentioned that he was a member of the movement. Perhaps he was ashamed of the way he had abandoned his own family in order to pursue this idealistic cul-de-sac. Quite how much money he contributed to the cause is unknown; nor is it known for how long he continued this arrangement. One assumes that his contributions petered out.

Much good work went on in the East End in the early years of the Twentieth Century but there were also projects that failed to deliver. When grand schemes and ideas are given more importance than the people whose lives they seek to improve, the result can be disastrous – quite apart from any accusations of rampant hypocrisy.

14/07/21

Full Steam Ahead - When We're Ready

I never thought I’d look with longing on the unremarkable reliability of an electrically-powered suburban train. But there I was, enviously watching the untroubled progress of the good old 11.19 from Norwood Junction to Victoria.

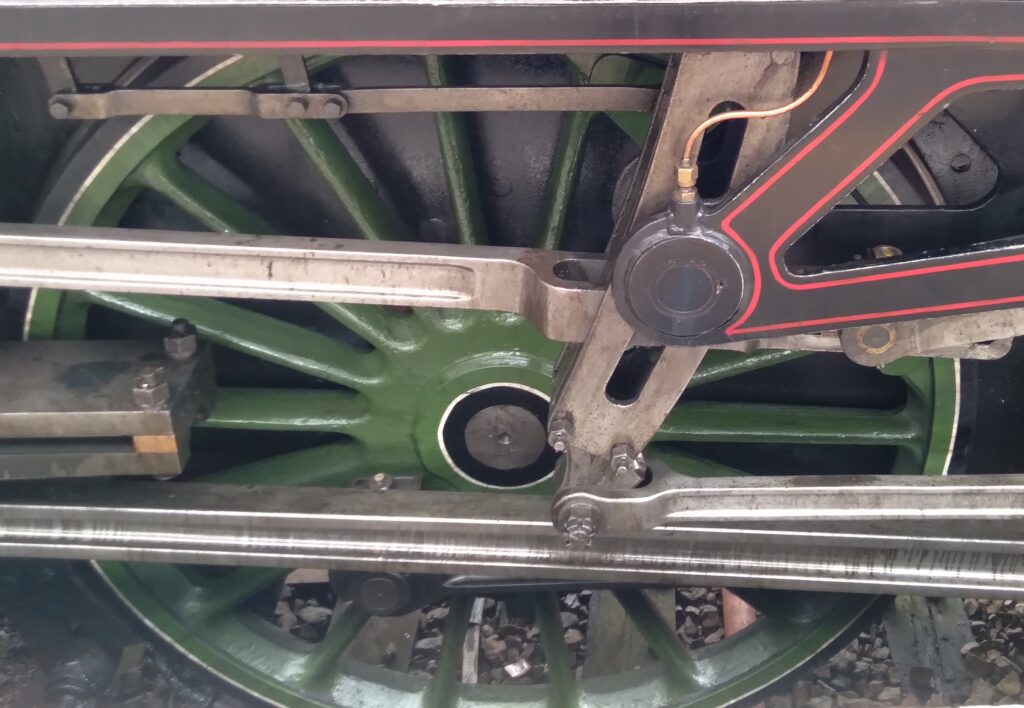

I had been stuck motionless on my train for almost two hours. The problem? Lack of water. The steam train excursion my partner and I had taken from Stratford in east London to the south coast and back was testing my patience to the limit. The only real curve we had negotiated successfully up to that point was of the steep learning variety.

Although I knew from my childhood train-spotting days at Hatfield on the L.N.E.R. line that steam locomotives had to take on water enroute I had no idea it was so often. Then a ferroequinologist (one of the new words I learned that day) sitting across the gangway from me explained: in former times every station, at the end of platforms, was equipped with a raised receptacle out of which dangled a pipe which filled the tanks of steam locomotives. The task was performed when the train had stopped to offload and pick up passengers and it was done in minutes without anyone really noticing. Nowadays, of course, there are no such facilities. So, what to do?

The company organising our trip had to hire bowsers (a re-learned word that one) to drive to various points where a road was in close proximity to the line, whereupon – why am I using such retro language in this article? Is my mind symbolically leafing through a dog-eared copy of the Chambers Dictionary in the search for ancient yet unambiguous vocabulary? If so, I blame the psychological power that my locomotive, the ex-L.N.E.R. B1 No. 61306 Mayflower, was having on me. Anyway … whereupon the bowser was required to park up and refill the engine’s water tanks.

But the lorry had broken down, phone calls were made (thank god for mobiles) and another was on its way. Well, it wasn’t actually on its way. It was stuck in Saturday morning traffic in the Wandsworth area. Our compartment was at the back and, as I leant out of the window, I could see the whole 10-carriage train at rest, carving a gentle arc towards Clapham Junction while an apologetic plume of smoke snaked up into the damp south London sky.

A fat controller (Well, I had to squeeze in a reference to Thomas the Tank Engine somehow) had the unenviable task of visiting every carriage to explain the reason for the hold-up. What did he say? ‘We should be on our way soon. I’m sorry about the delay.’ Well, of course he said that. I must say others were being more patient than I was. Ordering two plastic glasses of bucks fizz at 10.50am seemed to be the only answer.

Another downside of turning back the travel clock to the golden age of steam was dawning on me and I should have realised earlier. When you’re sitting on a train you don’t see the locomotive. Sometimes you hear the chugging or the whistle but those sounds echoing down through past eras are few and far between. Every photograph of a glamorous iron machine is taken by someone standing at a distance. Only at Stratford (and later at Eastbourne) as the Mayflower arrived in all its glory from Southend did I experience that unique thrill of being up close and personal with the steam beast. Another trick that nostalgia played on me.

Suddenly we were off. The bowser had done its work. We passed Balham and I thought of Peter Sellers’ travelogue sketch in which the place is pronounced with two distinct syllables – Bal-ham – and delivered with an American drawl. ‘Gateway to the south’. Well, we’ll see about that.

Soon we were picking up speed and careering into Surrey. This was better. Somewhere in Sussex we touched 76mph, my rail buff told me as he consulted his mobile phone which somehow was able to track the speed. Our apple green transport of delight swept past gardens and astonished passengers standing aghast on platforms. Most were young and this was probably their first steam train. And the loudspeaker announcement – ‘If you see something that doesn’t look right, speak to staff or text British Transport Police 61016. We’ll sort it. See it. Say it. Sorted’ had never been so appropriate. The driver had some fun and whistled ostentatiously, more often than he needed to. Gatwick went by in a flash.

To complete my fantasy return to the 1960s there was one more thing I had to do, which was to lean out of the window, turn towards the front of the train and wait for smut to lodge in my eye. In this ambition I was 100 per cent successful.

Going at this rollicking pace was a bonus; a steady 50mph had been the scheduled speed until the company decided to make up for lost time. Which it managed to do handsomely. I found out later that the rail authorities had given us priority on the line. Perhaps they just wanted this green-eyed monster out of the way as fast as possible. The South Downs hove (there comes that cute language again) into view. By the time we reached Eastbourne we had gained 50 minutes. It had been wonderfully exhilarating.

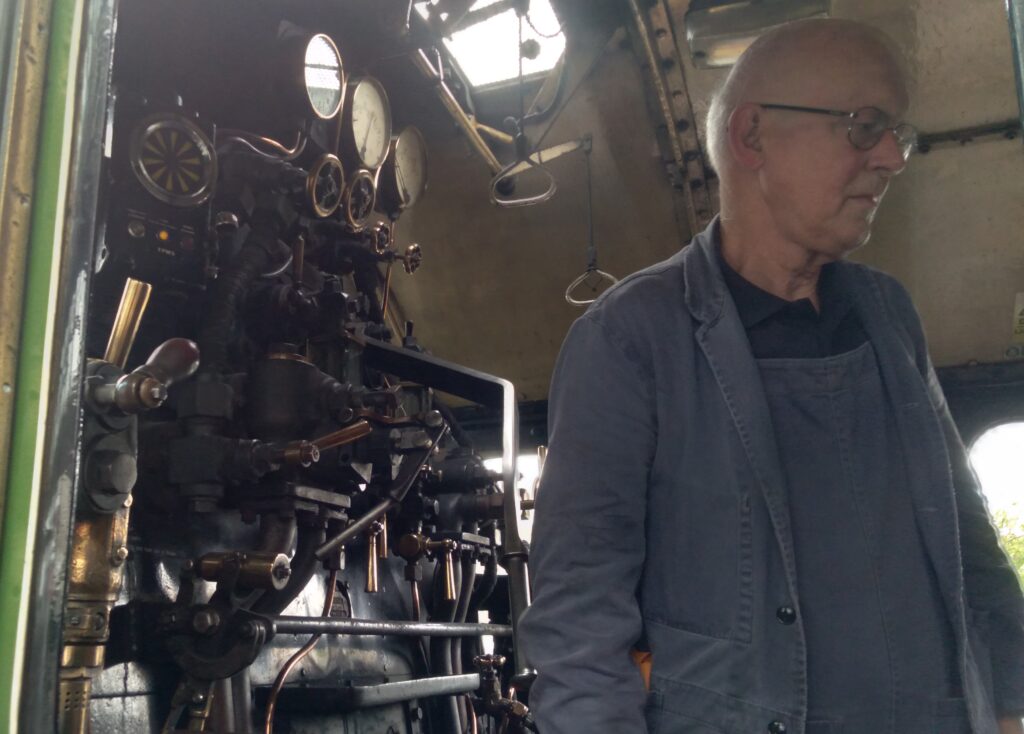

It was raining on the south coast, but we found a decent enough Italian restaurant and went for the excellent fish stew and a bottle of Pinot Grigio. We returned to the station and took some more shots in which the Mayflower was romantically shrouded in clouds of steam. I was reminded of the famous scene from Brief Encounter. Of course, I was. We asked the driver if we could mount the footplate, my request being inspired by all those times that my father in the late 1950s had asked the very same thing. There we were, watching the fireman stoke the boiler, minutes before our departure.

We returned via a different route further to the east, passing through Hastings, Battle and Tunbridge Wells before re-joining our original line at Redhill. But we missed out on the beauty of the East Sussex countryside because wine-induced sleep took over.

Houses and office blocks sprang up all around us. At Willesden South West Sidings the train stopped so that our trusty Mayflower could be uncoupled. She then – yes, I think a locomotive is feminine – returned to her home in Southall.

The no-nonsense purr of a diesel locomotive was the soundscape that accompanied us across north London and back to Stratford. Nondescript electric trains rattled by and this time I didn’t look on with envy at their seamless, computerised trajectory. The gaping passengers on platforms had gone. And there were the 21st century Canary Wharf skyscrapers glinting in the sun.

12/07/21

What About Italy’s Chances, Alan?

At half-time, during its coverage of the Euro 2020 final on Sunday, the BBC cut to footage of fans’ wild reactions to the second-minute goal. The riotous scenes in Croydon were accompanied by shots of a special-effects steam machine. Gary Lineker commented: ‘They’ll all be steaming later. That’s for sure.’

How wrong he was. England lost and not one of the assembled, so-called experts had predicted the likely Italian renaissance. It’s not the England players who need to hang their heads in shame. It’s the BBC’s four silly schoolboy pundits.

During the break they gave no credit to Italy, who had had 62 per cent possession with six attempts on goal to England’s one. Nor did they acknowledge the tactical brilliance of Roberto Mancini, who ended up turning the game around. And if they’d been observant, they might have noticed that that had already happened. Rio Ferdinand’s misplaced optimism was the worst. He actually said: ‘Italy haven’t got any players – apart from Chiesa – who can hurt us.’

Just before turning to the second-half action, Lineker commented: ‘Half-way there, folks.’ Then he asked Shearer: ‘Can they do it?’ Our mindless, folksy hero shot back: ‘Of course they can.’ By the way, have you noticed how Shearer has deliberately developed an Oxbridge-style stutter in a pathetic attempt to invest his simplistic analyses with more gravitas?

To give him his due, the slightly brighter Lampard (Well, he does have an A-level in Ancient Greek) did advise of the importance of England keeping their discipline.

My Irish friend Liam O’Sullivan told me: ‘I watched the half-time commentary on BBC, having watched the match on RTE. It’s like they were watching a different match entirely.’

All in all, it was shoddy journalism. Radio Five have been guilty of such juvenile analysis for years. Now it’s hit our TV screens.

Oh yes and, just for the record, the comments were underpinned by lashings of the usual jingoistic myopia. Plus ca change. It got me wondering where that bullet-headed nationalism emanates from? It could be part of these people’s make-up, of course. But do the programme’s producers have a pre-match editorial conference with the presenters and urge them to churn out no-holds-barred support for the home team at every opportunity? You see, it’s all about ratings, luv.

Another friend, Robin Hadley from Manchester, commented: ‘I watched ITV. At least Roy Keane and Gary Neville bring balance to their comments.’ Later I looked at ITV’s half-time analysis. Robin was right: Keane sounded a warning and Neville said England had to be brave. Anyway, with the adverts to show, the experts have less time to make idiots of themselves.

With each ridiculous statement on the BBC the friends I was watching with groaned more and more. Punditry was obviously a mug’s game. We wondered what the pay was like because clearly you didn’t need to be that expert at football to get on the panel.

The godlike Southgate had a bad game, but no one dared say it. Why did he choose to close down after half-time instead of going for another goal? As a Tottenham fan for 63 years, I know the idiocy of trying to defend a 1-0 lead. You can defend brilliantly (as England did) and still give away a goal from a corner (which they did).

The other mistake that the manager made was to ask those three youngsters (who had only just come on the pitch) to take responsibility for the penalties. Utter madness. Why didn’t more of the senior players step up?

But you can’t legislate for penalties. Anything can happen. The point is why didn’t England wrap it up earlier? Even as they were having that wonderfully dominant first 20 minutes, I knew in my bones that they needed another goal (bitter Spurs experience there again).

And all that talk about the England team uniting the country. What a load of piffle. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I tend to think it takes more than a few lads kicking a ball about rather well for five matches for that to happen.

Then after the defeat there was the throwing of bottles, the beating-up of fellow fans and the sickening racist abuse on social media. United? I rest my case.

02/06/21

Book Marketing Can Be Fun

Marketing was the last thing on my mind when I sat down to write my first book. Meticulous research, getting the right tone, maintaining the correct voice, and gauging the length were all greater priorities. Besides, there was always the chance I might find a mainstream publisher and they would do the promotion for me.

After two years my biography of my grandfather was complete. But I failed to grab the attention of a traditional publisher, so I was catapulted into the self-publishing arena. Which meant doing my own marketing. I approached the task with trepidation.

I searched websites to see if there was a realistic sales target for a first-time author. I compared my figures to those of J.K. Rowling. Every hour I checked the KDP/Amazon site to see if I’d sold another book. I fantasised about how my scintillating presentation would captivate booklovers in the elegant Edwardian surrounds of Daunts’ Marylebone premises and how I would sign numerous copies of my book with a kindly, maybe slightly patronising, smile as I asked the buyer to whom I should address the dedication. The books would fly off the shelves and the proceeds would cascade in like a tsunami.

Er. No. Marketing 2021 would prove to be an irksome business, focusing on the ins and outs of metadata, bibliographic detail, long synopses, short synopses, buzzwords, data optimisation, Facebook business pages, Twitter hashtags and Amazon reviews. I blundered in, not having a clue what I was doing, often breaking internet etiquette several times a day.

After six months in this darkened, digital labyrinth and adding IngramSpark to my Amazon presence – what the trade calls ‘going wide’ – I found I had sold 160 books by some means or other. Which quite a few people said was not bad. Heaven knows how I did it. And, even more surprising: I was beginning to enjoy it.

I had a sell sheet made – designed by Tony down the road – and everyone said it looked fantastic. It was something I could wave in the faces of indie bookshops and libraries, or else send as an attachment to book retailers all over the world. Its raison d’etre was to act as an inducement for them to order copies from the big distributors.

Because this period coincided with the easing of the Covid lockdown, I could joyfully walk away from my laptop and meet people face-to-face. Believe me, there are some snooty booksellers out there. One or two looked down their noses at my sell sheet and said imperiously: ‘Just leave it there.’ Others were as sweet as sweet could be. Like Denise Jones at the wonderful Brick Lane Bookshop in London. She stopped what she was doing and in 15 minutes I learned more about marketing for self-publishers than any number of online tutorials had taught me.

It was the unexpected avenues that opened up that began to make book marketing pleasant. Like Monty Dart, an authoress in Newport, south Wales, who having listened in on my talk to the local U3A group, helped me to do some promotion in her area and meet other local writers.

Next there were the animal photos. First author Ian Cutler gave me a great review and then took a shot of his cat Bronwyn taking a nap on my book. That just had to go on to Facebook. After that, my cousin Margie found her dog Honey ‘reading’ my biography and sent me a photo. That, too, was a marketing gift. My days as a subeditor on TV Times left me in no doubt that cute animal photos are loved by all.

Bookshops in Newton Abbot and worshippers at the Teignmouth church where Stanley, my grandfather, was a minister 120 years ago ordered copies on the strength of my eye-catching sell sheet.

And only yesterday Forest Gate author John Walker said I should persuade friends to go into libraries and ask for my book. That was a sure-fire way of shifting a few more copies because one thing libraries want to do is please their customers.

I’m still embroiled in metadata, social media and Zoom. But now I’ve added person-to-person marketing to the mix. My only hope is that for us downtrodden stay-at-homes it catches on.

11/05/21

Road to a Nightingale

I bet John Keats never had to negotiate the Brentwood by-pass ro get to hear his ‘light-winged Dryad of the trees’. His nightingale obligingly perched a few yards away in a nearby tree on Hampstead Heath before singing ‘in full-throated ease’. Our melancholy young Cockney medic probably didn’t even have to stir from the comfort of his leather armchair. All he had to do was sit back and listen as the bird’s ‘plaintive anthem’ poured in through the open French windows of his north London gaff.

We, on the other hand, to hear our nightingale, left east London by car on a Friday afternoon. Within minutes we hit an end-of-the-week and end of Covid restrictions snarl-up on the A12, just beyond the Redbridge roundabout. We were heading for the Fingringhoe bird reserve on a raised area of wild land above the banks of the Colne Estuary.

The traffic jams continued for miles, and it was two and a half hours before we made our destination. A helpful couple out walking their dog directed us down the narrow lane and confirmed the reserve’s pledge that the birds were singing by assuring us they had stopped to listen to them just 30 minutes before.

The reserve had closed at 5pm, but we parked on a convenient patch of bare ground next to the padlocked gates, ate our sandwiches and sipped tea from our thermos flask. Here, all around us, were plenty of ‘melodious plots of beechen green and shadows numberless’ – just the kind of landscape that nightingales like.