I’m a childless man – at 72, not being a father is my biggest life regret

by Robert Nurden, The i, 11 July 2023

The family of four looked in high spirits on their jaunt into central London. The kids were pulling faces and snatching each other’s iPhones as the chilled parents looked on. The scene that played out on the train seats opposite me was so normal that it verged on the banal. We exchanged watery smiles across the aisle.

Then it hit me. Run-of-the-mill it might have been but my life was as far removed from this domestic drama as it was possible to be. I have no children, and at 72 I never will have. Just when I thought I had come to accept my loss, decades of mute grief came flooding back.

The gut punch that such displays of happy family life can inflict on me is a familiar one for many men and women who don’t have the children that they always dreamed of having, whether that is due to infertility, poor judgement or just bad luck.

This gut punch is not just loneliness; I have a partner who has grown-up children and I have many friends. But my life is fundamentally different because I am not the father that I expected to be. I missed out on parenthood, the social status that brings, the responsibility, the opportunity for caring and nurturing, the legacy of children and grandchildren, and having these people to look after me in later years.

Quite naturally, this issue of unwanted childlessness mostly focuses on women. The trope basically goes that men don’t ever want children (not really) and when they end up with them it is because a woman twisted their arm to have them. Not true! At least not any more. Men can feel just as deprived as women when this doesn’t happen. I know: I’m one of them.

The phenomenon of male childlessness is more widespread than society acknowledges. Some 25 per cent of men over 42 are childless, according to Dr Robin Hadley’s book, How is a Man Supposed to be a Man?. The numbers are growing, which has massive implications for health and social care provision. It has to be said, of course, that many thousands of adults remain child-free by choice.

But for those who wanted children but life didn’t work out that way, the triggers are everywhere. Childless men dread Father’s Day. I usually hunker down and read a good book. The advertising industry is geared towards the ideal family. Chats at work about one’s colleagues’ children are commonplace and driving past schools as parents collect their kids can hurt; everyday ambushes like these can plunge a dagger into the heart of the parentless.

I regret so much in my life. I look back at wrong turns, poor decision-making, bad timing. Should I have worked harder at making a relationship work? Should an ex-girlfriend and I have decided that she should have an abortion? Later on, there was a miscarriage. Then there was a broken engagement.

I just thought it would happen, so I blame myself for complacency. I look at my friends who never wanted to be dads yet have four to whom they devote a scant amount of time. There are the hardly-there fathers – alcoholics, absentees, adulterers, abusers or just not very good ones – and you wonder if you would have done a better job.

I first started to get broody in my early forties. The problem was potential partners were the same age and were divorced and either had children and didn’t want more, or were past the age of having children. I could have settled for a compatible but childless relationship but I still wanted my own kids.

Traditionally, men want to leave a legacy by seeing the family name continue. Those who are not fathers often find a substitute activity such as teaching, nursing, charity work or sponsoring a child to try and fill that yawning gap. I returned to teaching but it was nothing like caring for one’s own offspring.

So, why didn’t it happen? Why will no child of mine ever phone up and say: “Hi, Dad! How are you?” Dr Hadley suggests that one may need to go back to one’s childhood to find part of the answer. Anxiety over early years’ attachments with one’s care-givers may cause one to have problems with trust. That certainly resonates with me.

Is it all too late for me, then? Yes, basically. It’s time to clear up the widespread view that men can procreate with ease into old age. Statistics show that fewer than two per cent of fathers are 50 or over (in 2013 this was 1.25 per cent according to the ONS). The Mick Jaggers of this world are a rare species. Quite apart from a stack of evidence showing the medical dangers of fathering late in life.

There are upsides. I have the freedom to do things fathers can’t do. I belong to a Facebook group called the Childless Men’s Community, which is very supportive. And I have written a book. Here I am meant to fashion a neat conclusion but there isn’t one – except of course to say that you can never have everything you want.

‘I just assumed it would happen’: the unspoken grief of childless men

A quarter of UK men over 42 do not have children. When that is not by choice, regret can grow into pain

by Amelia Hill, The Guardian, 28 August 2023

Father’s Day is dangerous for Robert Nurden. Childless not through choice but, as he puts it, “complacency, bad luck, bad judgment”, he tries to stay indoors and ignore the family celebrations outside.

But one year, he went for a walk. “I met family after family. There were children everywhere,” he remembered. “It was terrible. Just so painful. So many ambushes and triggers for my anguish.”

There is very little research into men who have not had children, although that is beginning to change. Research by Dr Robin Hadley has found that 25% of men over 42 do not have children – 5% more than women of the same age group.

Half of the men who are not fathers but wanted to be describe a huge grief and isolation from society. Almost 40% have experienced depression and a quarter feel a deep anger.

Now 72, Nurden had a sheltered upbringing. Reaching adulthood, there was a lot he wanted to experience. “Having children was a very low priority. I was complacent: I just assumed it would happen,” he said.

It was not until he was in his early 40s that Nurden started to get broody. But by that point, he discovered, women of a similar age had already had children, if they were able or wanted to.

“I went into this 15-year period of not going into relationships or ending relationships quickly because I knew that person wasn’t going to want or be able to have a child with me – or that the relationship wasn’t going to be strong enough to last if we did have a child,” said Nurden.

He said high-profile older fathers breed complacency in ordinary men. “If I’m honest, even when I was in my 50s I believed that it might happen for me,. But in real life, the Mick Jagger and Jon Snow-age fathers are actually very rare – and in any case, it’s medically not wise, as regards sperm quality.”

What compounded Nurden’s pain was that there was no public or private discussion about how men feel when circumstance leaves them unable to become fathers.

“There’s lots of publicity, quite rightly, about women and childlessness but men are very mute about this. Married men don’t want to hear it either: I’ve had men with children react with anger, as though they feel threatened, when I’ve tried to talk about my pain,” he said.

“I was mute too until recently, because as I aged, I found the regret grew into a great pain,” he added. “Unlike many other forms of grief, this compounds itself as it gets older: I wasn’t a father but now I’m not a grandfather. When I’m even older, I might find myself entirely alone.”

Nurden has published a book, I Always Wanted to be a Dad: Men Without Children, about his story and that of some other men. “It turns out that there is a lot of pain, regret and sadness out there,” he said.

Hadley, the researcher, is childless because his wife never wanted children. “I chose love but that doesn’t make the pain of not having children any less,” he said. “When a close colleague had his first child, I was so jealous that I couldn’t be in the same room as him.”

Being a father is a marker of status in many countries, said Hadley, but not in the west. “While there has recently been a lot more public discussion about how to be a good father, we still don’t have any narrative or celebration about how important it is for men to become a father in the first place,” he said.

Paul Goulden, the chair of Ageing Without Children, said that, along with the lack of public dialogue about becoming a father, he was “not convinced that there’s this Game of Thrones genetic push felt by men to have children”.

Instead, he said: “There’s this mistaken belief that men are fertile across their lifespan, so there’s no imperative to get on with it.”

That complacency persists because men without children historically have not spoken about their grief. But, Goulden said: “I hope Robert’s book will trigger a change in public dialogue around this issue. I think there’s an overwhelming sense of loneliness and fear out there about who is going to be there for these men, when they’re old and all alone.”

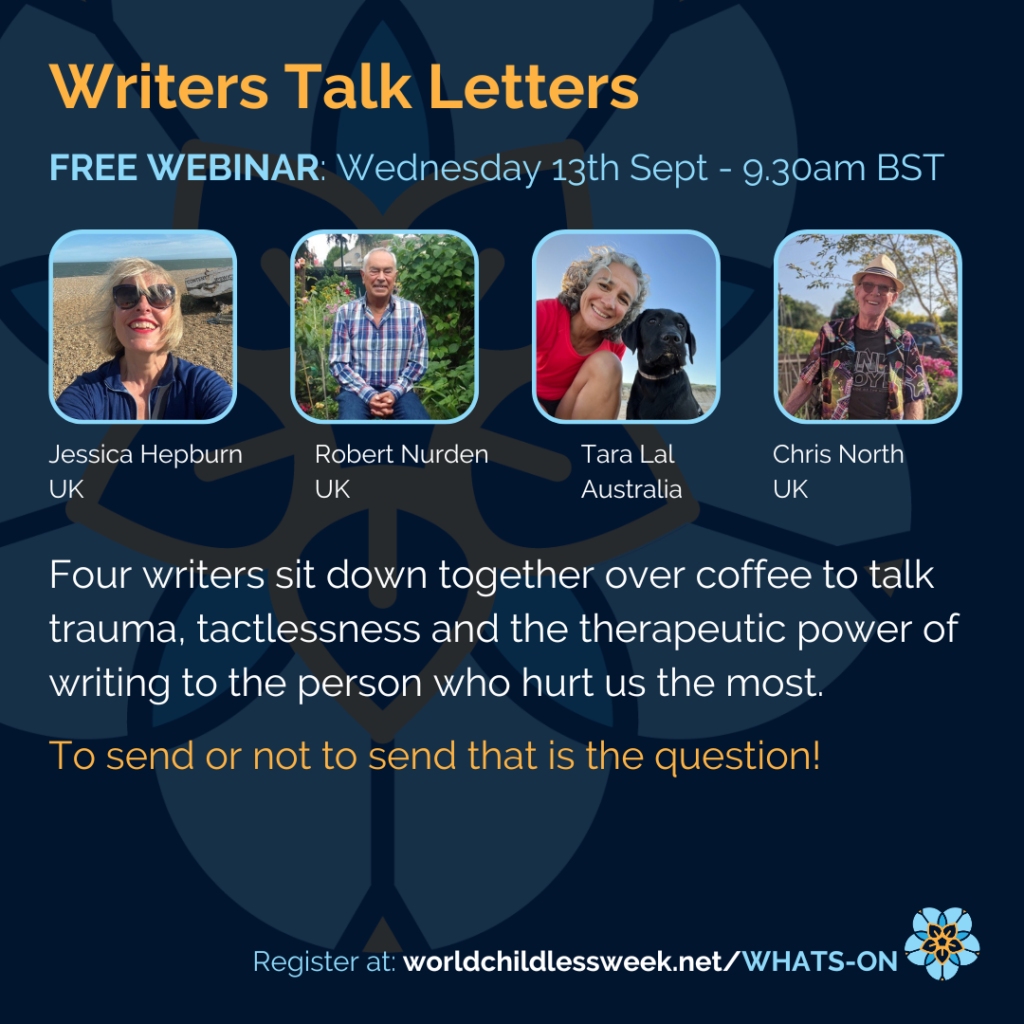

This month, meet Robert Nurden. You may have read about him in The Guardian, Independent or heard him on BBC Scotland with Dr Robin Hadley.

Join us as we venture into an intimate conversation covering his career in journalism and teaching, and an important cup of Americano; Robert’s journey is far from ordinary. We talk about how he transitioned from journalism to teaching English around the world and his life as an author.

Our conversation delves deeper into Robert’s personal story, tackling the sensitive topic of men without children. He shares how he found support in The Childless Men’s Community and how this experience inspired him to create a play titled Empty which lead to the writing of I Always Wanted To Be A Dad: Men Without Children, featuring Robert’s writing and a powerful collection of testimonials from men who find themselves without children too.