Stanley James, my grandfather, was born in Bristol in 1869. His father, a Congregational minister, wanted him to become a pastor, too. Although he enrolled for several ministry training courses, he quit them all. He lurched from one unfulfilling teaching job to another, on one occasion sharing lodgings with the fiery Chartist, George Julian Harney and bumping into Friedrich Engels. He even tried his hand at becoming an actor, with disastrous results.

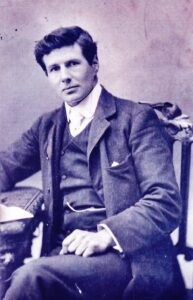

In despair he emigrated with his brother Norman to Canada, arriving in April 1893. He spent the next four years as a cowboy in the shadow of the Rockies. His horse-handling skills were eventually good enough for him to join the round-ups and branding sessions. He penned poems about life as a lonely ranch hand and wrote farces for his mates, including himself, to perform in the local schoolhouse during the long, winter evenings. He became the Calgary Herald correspondent for his district, embarrassing local politicians with his too truthful reports. Beneath the surface his spiritual quest continued.

In 1897 the Herald editor offered him a job, during which he masterminded a supplement targeted at Klondike gold prospectors. But he refused to give favourable coverage to advertisers and the editor fired him. Penniless, he walked 120 miles to Lethbridge where he hoped to land a job as minder for cattle being shipped to England – but missed the train. He sold toiletries to navvies on the Crow’s Nest Pass Railway, then became a navvy himself.

A friend was returning to Toronto as a hobo and asked Stanley to join him. They rode the rods, jumping on, and getting thrown off, trains. He headed for Buffalo, enlisted in the US army and fought in the Spanish-American war of 1898. He saw action in Cuba and Puerto Rico, contracted dysentery (or possibly yellow fever) and nearly died.

Shipped out, he convalesced in a New York military hospital, where he re-read the Bible and claimed to hear the voice of God. He returned to England and found his father, now a minister in Wimbledon, dying. Without any ecclesiastical qualifications, he took over the sermon slot and preached. ‘The egotism of the pulpit was in my veins,’ he wrote.

Then he met Jess, my grandmother, fell in love and became engaged. She lived in the Chilterns so after Sunday services he cycled 50 miles through the night to see her. His first ministry was in a seaside town in Devon, which was where the first four children were born. Although his uncompromising, left-wing politics was making itself felt, these were years of relative calm.

He moved to Trinity Church, Walthamstow, in 1906 and immediately rocked the boat. He split the congregation with his communist and suffragist leanings and love for any radical religious movement going. Someone referred to him as a ‘rotter’, another as a ‘dipper’, meaning he dipped in and out of every trend of the moment. In 1914 his passionate pacifist sermons proved to be his downfall.

But not before falling in love with Eva Slawson, who loved him in turn before she died of undetected diabetes in 1915. Then Stanley seduced Eva’s best friend Minna Simmons, another beauty in his congregation. Minna wrote to her friend Ruth Slate: ‘Well, dear, we went into the front room alone and he kissed me, opened my dress and kissed my breasts too and he said how he felt I was his. He was just going away when he came back and pleaded with me to give him everything a woman can give a man. I told him I was sure we should regret it but anything that would make me his. Well, dear, I did.’ That letter is included in The Virago Book of Love Letters, placed between one from Maud Gonne to the poet W.B Yeats and another from Violet Trefusis to Vita Sackville-West. Weeks later he was writing love letters to Ruth.

He visited Ireland and wrote reports for the English press on the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Uprising. The church was in turmoil and in November the deacons forced him to resign: his pacifism had alienated too many. He set up an alternative church, one that leaned towards communism and allied itself to the Brotherhood Church in Hackney. He then worked alongside Bertrand Russell at the No Conscription Fellowship, which the police raided on a regular basis. Next came the Fellowship of Reconciliation where he clashed with Quakers whom he accused of being ‘too gentle’. Nevertheless, ever the Christian chameleon, and despite the family never having any money, he donated sums of money to the Voluntary Poverty movement.

He started writing for – and became editor of – The Crusader, a pacifist Christian journal, which the police also raided. Here he clashed with, and eventually lost, his contributors, including Conrad Noel, the ‘Red Vicar of Thaxted’, whose communist church Stanley preached at. He turned to King’s Weigh House, an ecclesiastical experiment seeking to combine the best of Catholicism with the best of Protestantism under the leadership of Dr Orchard. He eventually became a Catholic in 1923 and counted G.K. Chesterton among his friends. On publication of his autobiography, The Adventures of a Spiritual Tramp, the celebrated artist Dame Laura Knight invited him to tea with W.H. Davies who had earlier written The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp. The former vagabonds compared notes.

In his garden shed, first in Hampshire and later in Hertfordshire, using a decrepit old typewriter and wreathed in tobacco smoke, he turned himself into one of the most celebrated and best-loved Catholic writers of his generation, writing for over 20 publications. Although he claimed to have found the authority and spiritual peace he had craved for over half his life, all was not well at home. He tried to force his family – against their wishes – to convert to Catholicism, but most resisted. ‘He tore the family apart,’ one aunt told me.

He died in November 1951 from stomach cancer. The inscription on his headstone symbolises the ideological contradictions that marked his life. It says: ‘Strong and Content I Travel the Open Road’, a line from Walt Whitman, Stanley’s favourite pagan poet from his days as a tramp. There is no reference to his Christian beliefs or to his wife and seven children. His Times and Catholic Herald obituaries spoke of his kindness, his intellect and his learning. But these exclusively male writers knew only half the story, not least that of his long-suffering wife. Stanley James, a complex man, remains an enigma, caught Between Heaven and Earth.